How to make the best of the most important century?

Previously in the "most important century" series, I've argued that there's a high probability1 that the coming decades will see:

- The development of a technology like PASTA (process for automating scientific and technological advancement).

- A resulting productivity explosion leading to development of further transformative technologies.

- The seed of a stable galaxy-wide civilization, possibly featuring digital people, or possibly run by misaligned AI.

Is this an optimistic view of the world, or a pessimistic one? To me, it's both and neither, because this set of events could end up being very good or very bad for the world, depending on the details of how it plays out.

When I talk about being in the "most important century," I don't just mean that significant events are going to occur. I mean that we, the people living in this century, have the chance to have a huge impact on huge numbers of people to come - if we can make sense of the situation enough to find helpful actions.

But it's also important to understand why that's a big "if" - why the most important century presents a challenging strategic picture, such that many things we can do might make things better or worse (and it's hard to say which).

In this post, I will present two contrasting frames for how to make the best of the most important century:

- The "Caution" frame. In this frame, many of the worst outcomes come from developing something like PASTA in a way that is too fast, rushed, or reckless. We may need to achieve (possibly global) coordination in order to mitigate pressures to race, and take appropriate care. (Caution)

- The "Competition" frame. This frame focuses not on how and when PASTA is developed, but who (which governments, which companies, etc.) is first in line to benefit from the resulting productivity explosion. (Competition)

- People who take the "caution" frame and people who take the "competition" frame often favor very different, even contradictory actions. Actions that look important to people in one frame often look actively harmful to people in the other.

- I worry that the "competition" frame will be overrated by default, and discuss why below. (More)

- To gain more clarity on how to weigh these frames and what actions are most likely to be helpful, we need more progress on open questions about the size of different types of risks from transformative AI. (Open questions)

- In the meantime, there are some robustly helpful actions that seem likely to improve humanity's prospects regardless. (Robustly helpful actions)

The "caution" frame

I've argued for a good chance that this century will see a transition to a world where digital people or misaligned AI (or something else very different from today's humans) are the major force in world events.

The "caution" frame emphasizes that some types of transition seem better than others. Listed in order from worst to best:

Worst: Misaligned AI

I discussed this possibility previously, drawing on a number of other and more thorough discussions.2 The basic idea is that AI systems could end up with objectives of their own, and could seek to expand throughout space fulfilling these objectives. Humans, and/or all humans value, could be sidelined (or driven extinct, if we'd otherwise get in the way).

Next-worst:3 Adversarial Technological Maturity

If we get to the point where there are digital people and/or (non-misaligned) AIs that can copy themselves without limit, and expand throughout space, there might be intense pressure to move - and multiply (via copying) - as fast as possible in order to gain more influence over the world. This might lead to different countries/coalitions furiously trying to outpace each other, and/or to outright military conflict, knowing that a lot could be at stake in a short time.

I would expect this sort of dynamic to risk a lot of the galaxy ending up in a bad state.4

One such bad state would be "permanently under the control of a single (digital) person (and/or their copies)." Due to the potential of digital people to create stable civilizations, it seems that a given totalitarian regime could end up permanently entrenched across substantial parts of the galaxy.

People/countries/coalitions who suspect each other of posing this sort of danger - of potentially establishing stable civilizations under their control - might compete and/or attack each other early on to prevent this. This could lead to war with difficult-to-predict outcomes (due to the difficult-to-predict technological advancements that PASTA could bring about).

Second-best: Negotiation and governance

Countries might prevent this sort of Adversarial Technological Maturity dynamic by planning ahead and negotiating with each other. For example, perhaps each country - or each person - could be allowed to create a certain number of digital people (subject to human rights protections and other regulations), limited to a certain region of space.

It seems there are a huge range of different potential specifics here, some much more good and just than others.

Best: Reflection

The world could achieve a high enough level of coordination to delay any irreversible steps (including kicking off an Adversarial Technological Maturity dynamic).

There could then be something like what Toby Ord (in The Precipice) calls the "Long Reflection":5 a sustained period in which people could collectively decide upon goals and hopes for the future, ideally representing the most fair available compromise between different perspectives. Advanced technology could imaginably help this go much better than it could today.6

There are limitless questions about how such a "reflection" would work, and whether there's really any hope that it could reach a reasonably good and fair outcome. Details like "what sorts of digital people are created first" could be enormously important. There is currently little discussion of this sort of topic.7

Other

There are probably many possible types of transitions I haven't named here.

The role of caution

If the above ordering is correct, then the future of the galaxy looks better to the extent that:

- Misaligned AI is avoided: powerful AI systems act to help humans, rather than pursuing objectives of their own.

- Adversarial Technological Maturity is avoided. This likely means that people do not deploy advanced AI systems, or the technologies they could bring about, in adversarial ways (unless this ends up necessary to prevent something worse).

- Enough coordination is achieved so that key players can "take their time," and Reflection becomes a possibility.

Ideally, everyone with the potential to build something PASTA-like would be able to pour energy into building something safe (not misaligned), and carefully planning out (and negotiating with others on) how to roll it out, without a rush or a race. With this in mind, perhaps we should be doing things like:

- Working to improve trust and cooperation between major world powers. Perhaps via AI-centric versions of Pugwash (an international conference aimed at reducing the risk of military conflict), perhaps by pushing back against hawkish foreign relations moves.

- Discouraging governments and investors from shoveling money into AI research, encouraging AI labs to thoroughly consider the implications of their research before publishing it or scaling it up, etc. Slowing things down in this manner could buy more time to do research on avoiding misaligned AI, more time to build trust and cooperation mechanisms, more time to generally gain strategic clarity, and a lower likelihood of the Adversarial Technological Maturity dynamic.

The "competition" frame

(Note: there's some potential for confusion between the "competition" idea and the Adversarial Technological Maturity idea, so I've tried to use very different terms. I spell out the contrast in a footnote.8)

The "competition" frame focuses less on how the transition to a radically different future happens, and more on who's making the key decisions as it happens.

- If something like PASTA is developed primarily (or first) in country X, then the government of country X could be making a lot of crucial decisions about whether and how to regulate a potential explosion of new technologies.

- In addition, the people and organizations leading the way on AI and other technology advancement at that time could be especially influential in such decisions.

This means it could matter enormously "who leads the way on transformative AI" - which country or countries, which people or organizations.

- Will the governments leading the way on transformative AI be authoritarian regimes?

- Which governments are most likely to (effectively) have a reasonable understanding of the risks and stakes, when making key decisions?

- Which governments are least likely to try to use advanced technology for entrenching the power and dominance of one group? (Unfortunately, I can't say there are any that I feel great about here.) Which are most likely to leave the possibility open for something like "avoiding locked-in outcomes, leaving time for general progress worldwide to raise the odds of a good outcome for everyone possible?"

- Similar questions apply to the people and organizations leading the way on transformative AI. Which ones are most likely to push things in a positive direction?

Some people feel that we can make confident statements today about which specific countries, and/or which people and organizations, we should hope lead the way on transformative AI. These people might advocate for actions like:

- Increasing the odds that the first PASTA systems are built in countries that are e.g. less authoritarian, which could mean e.g. pushing for more investment and attention to AI development in these countries.

- Supporting and trying to speed up AI labs run by people who are likely to make wise decisions (about things like how to engage with governments, what AI systems to publish and deploy vs. keep secret, etc.)

Why I fear "competition" being overrated, relative to "caution"

By default, I expect a lot of people to gravitate toward the "competition" frame rather than the "caution" frame - for reasons that I don't think are great, such as:

- I think people naturally get more animated about "helping the good guys beat the bad guys" than about "helping all of us avoid getting a universally bad outcome, for impersonal reasons such as 'we designed sloppy AI systems' or 'we created a dynamic in which haste and aggression are rewarded.'"

- I expect people will tend to be overconfident about which countries, organizations or people they see as the "good guys."

- Embracing the "competition" frame tends to point toward taking actions - such as working to speed up a particular country's or organization's AI development - that are lucrative, exciting and naturally easy to feel energy for. Embracing the "caution" frame is much less this way.

- The biggest concerns that the "caution" frame focuses on - Misaligned AI and Adversarial Technological Maturity - are a bit abstract and hard to wrap one's head around. In many ways they seem to be the highest-stakes risks, but it's easier to be viscerally scared of "falling behind countries/organizations/people that scare me" than to be viscerally scared of something like "Getting a bad outcome for the long-run future of the galaxy because we rushed things this century."

- I think Misaligned AI is a particularly hard risk for many to take seriously. It sounds wacky and sci-fi-like; people who worry about it tend to be interpreted as picturing something like The Terminator, and it can be hard for their more detailed concerns to be understood.

- I'm hoping to run more posts in the future that help give an intuitive sense for why I think Misaligned AI is a real risk.

So for the avoidance of doubt, I'll state that I think the "caution" frame has an awful lot going for it. In particular, Misaligned AI and Adversarial Technological Maturity seem a lot worse than other potential transition types, and both seem like things that have a real chance of making the entire future of our species (and successors) much worse than they could be.

I worry that too much of the "competition" frame will lead to downplaying misalignment risk and rushing to deploy unsafe, unpredictable systems, which could have many negative consequences.

With that said, I put serious weight on both frames. I remain quite uncertain overall about which frame is more important and helpful (if either is).

Key open questions for "caution" vs. "competition"

People who take the "caution" frame and people who take the "competition" frame often favor very different, even contradictory actions. Actions that look important to people in one frame often look actively harmful to people in the other.

For example, people in the "competition" frame often favor moving forward as fast as possible on developing more powerful AI systems; for people in the "caution" frame, haste is one of the main things to avoid. People in the "competition" frame often favor adversarial foreign relations, while people in the "caution" frame often want foreign relations to be more cooperative.

(That said, this dichotomy is a simplification. Many people - including myself - resonate with both frames. And either frame could imply actions normally associated with the other; for example, you might take the "caution" frame but feel that haste is needed now in order to establish one country with a clear enough lead in AI that it can then take its time, prioritize avoiding misaligned AI, etc.)

I wish I could confidently tell you how much weight to put on each frame, and what actions are most likely to be helpful. But I can't. I think we would have more clarity if we had better answers to some key open questions:

Open question: how hard is the alignment problem?

The path to the future that seems worst is Misaligned AI, in which AI systems end up with non-human-compatible objectives of their own and seek to fill the galaxy according to those objectives. How seriously should we take this risk - how hard will it be to avoid this outcome? How hard will it be to solve the "alignment problem," which essentially means having the technical ability to build systems that won't do this?9

- Some people believe that the alignment problem will be formidable; that our only hope of solving it comes in a world where we have enormous amounts of time and aren't in a race to deploy advanced AI; and that avoiding the "Misaligned AI" outcome should be by far the dominant consideration for the most important century. These people tend to heavily favor the "caution" interventions described above: they believe that rushing toward AI development raises our already-substantial risk of the worst possible outcome.

- Some people believe it will be easy, and/or that the whole idea of "misaligned AI" is misguided, silly, or even incoherent - planning for an overly specific future event. These people often are more interested in the "competition" interventions described above: they believe that advanced AI will probably be used effectively by whatever country (or in some cases smaller coalition or company) develops it first, and so the question is who will develop it first.

- And many people are somewhere in between.

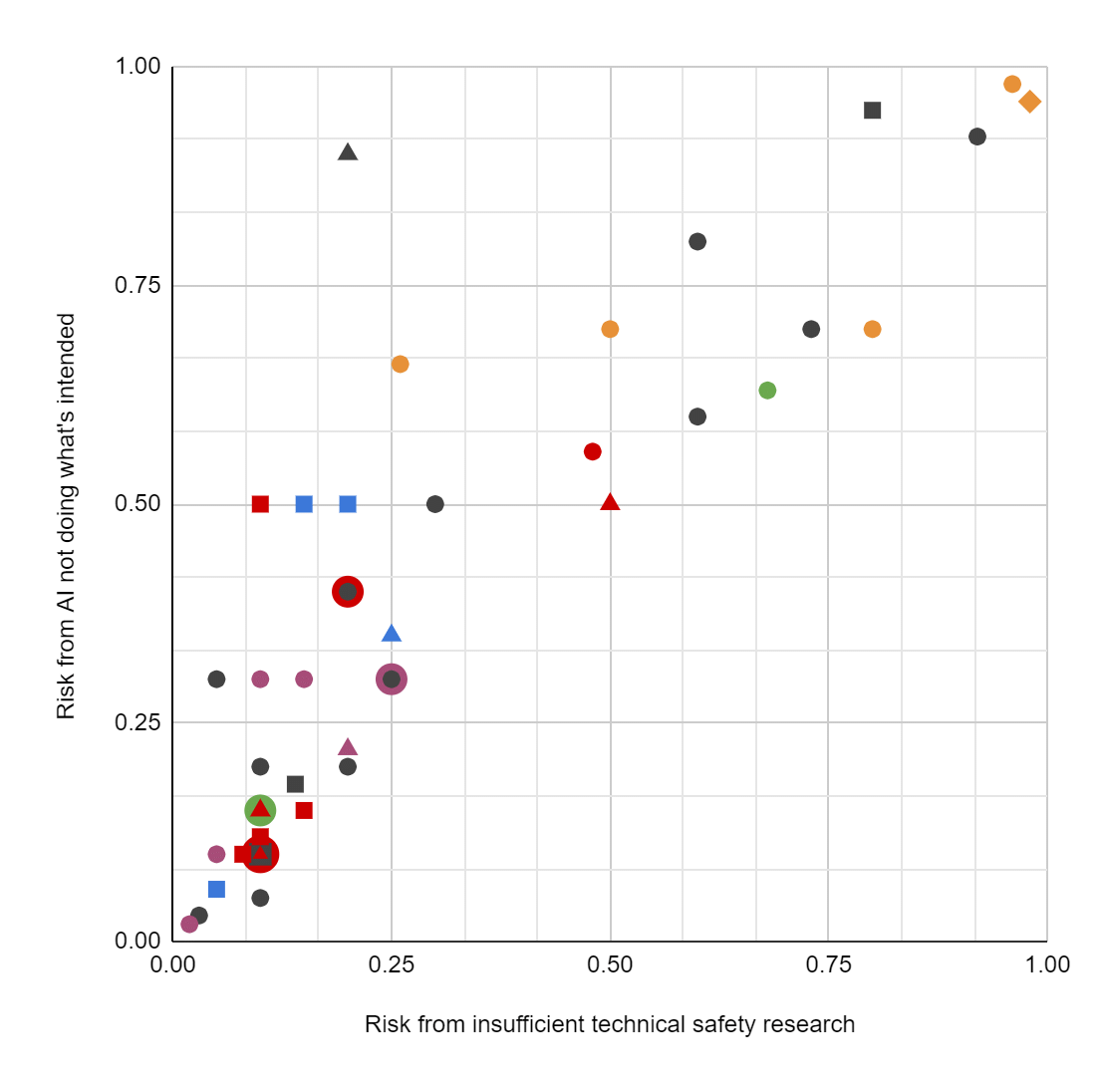

The spread here is extreme. For example, see these results from an informal "two-question survey [sent] to ~117 people working on long-term AI risk, asking about the level of existential risk from 'humanity not doing enough technical AI safety research' and from 'AI systems not doing/optimizing what the people deploying them wanted/intended.'" (As the scatterplot shows, people gave similar answers to the two questions.)

We have respondents who think there's a <5% chance that alignment issues will drastically reduce the goodness of the future; respondents who think there's a >95% chance; and just about everything in between.10 My sense is that this is a fair representation of the situation: even among the few people who have spent the most time thinking about these matters, there is practically no consensus or convergence on how hard the alignment problem will be.

I hope that over time, the field of people doing research on AI alignment11 will grow, and as both AI and AI alignment research advance, we will gain clarity on the difficulty of the AI alignment problem. This, in turn, could give more clarity on prioritizing "caution" vs. "competition."

Other open questions

Even if we had clarity on the difficulty of the alignment problem, a lot of thorny questions would remain.

Should we be expecting transformative AI within the next 10-20 years, or much later? Will the leading AI systems go from very limited to very capable quickly ("hard takeoff") or gradually ("slow takeoff")?12 Should we hope that government projects play a major role in AI development, or that transformative AI primarily emerges from the private sector? Are some governments more likely than others to work toward transformative AI being used carefully, inclusively and humanely? What should we hope a government (or company) literally does if it gains the ability to dramatically accelerate scientific and technological advancement via AI?

With these questions and others in mind, it's often very hard to look at some action - like starting a new AI lab, advocating for more caution and safeguards in today's AI development, etc. - and say whether it raises the likelihood of good long-run outcomes.

Robustly helpful actions

Despite this state of uncertainty, here are a few things that do seem clearly valuable to do today:

Technical research on the alignment problem. Some researchers work on building AI systems that can get "better results" (winning more board games, classifying more images correctly, etc.) But a smaller set of researchers works on things like:

- Training AI systems to incorporate human feedback into how they perform summarization tasks, so that the AI systems reflect hard-to-define human preferences - something it may be important to be able to do in the future.

- Figuring out how to understand "what AI systems are thinking and how they're reasoning," in order to make them less mysterious.

- Figuring out how to stop AI systems from making extremely bad judgments on images designed to fool them, and other work focused on helping avoid the "worst case" behaviors of AI systems.

- Theoretical work on how an AI system might be very advanced, yet not be unpredictable in the wrong ways.

This sort of work could both reduce the risk of the Misaligned AI outcome - and/or lead to more clarity on just how big a threat it is. Some takes place in academia, some at AI labs, and some at specialized organizations.

Pursuit of strategic clarity: doing research that could address other crucial questions (such as those listed above), to help clarify what sorts of immediate actions seem most useful.

Helping governments and societies become, well, nicer. Helping Country X get ahead of others on AI development could make things better or worse, for reasons given above. But it seems robustly good to work toward a Country X with better, more inclusive values, and a government whose key decision-makers are more likely to make thoughtful, good-values-driven decisions.

Spreading ideas and building communities. Today, it seems to me that the world is extremely short on people who share certain basic expectations and concerns, such as:

- Believing that AI research could lead to rapid, radical changes of the extreme kind laid out here (well beyond things like e.g. increasing unemployment).

- Believing that the alignment problem (discussed above) is at least plausibly a real concern, and taking the "caution" frame seriously.

- Looking at the whole situation through a lens of "Let's get the best outcome possible for the whole world over the long future," as opposed to more common lenses such as "Let's try to make money" or "Let's try to ensure that my home country leads the world in AI research."

I think it's very valuable for there to be more people with this basic lens, particularly working for AI labs and governments. If and when we have more strategic clarity about what actions could maximize the odds of the "most important century" going well, I expect such people to be relatively well-positioned to be helpful.

A number of organizations and people have worked to expose people to the lens above, and help them meet others who share it. I think a good amount of progress (in terms of growing communities) has come from this.

Donating? One can donate today to places like this. But I need to admit that very broadly speaking, there's no easy translation right now between "money" and "improving the odds that the most important century goes well." It's not the case that if one simply sent, say, $1 trillion to the right place, we could all breathe easy about challenges like the alignment problem and risks of digital dystopias.

It seems to me that we - as a species - are currently terribly short on people who are paying any attention to the most important challenges ahead of us, and haven't done the work to have good strategic clarity about what tangible actions to take. We can't solve this problem by throwing money at it.13 First, we need to take it more seriously and understand it better.

Next (and last) in series: Call to Vigilance

Use "Feedback" if you have comments/suggestions you want me to see, or if you're up for giving some quick feedback about this post (which I greatly appreciate!) Use "Forum" if you want to discuss this post publicly on the Effective Altruism Forum.

Footnotes

-

From Forecasting Transformative AI: What's the Burden of Proof?: "I am forecasting more than a 10% chance transformative AI will be developed within 15 years (by 2036); a ~50% chance it will be developed within 40 years (by 2060); and a ~2/3 chance it will be developed this century (by 2100)."

Also see Some additional detail on what I mean by "most important century." ↩

-

These include the books Superintelligence, Human Compatible, Life 3.0, and The Alignment Problem. The shortest, most accessible presentation I know of is The case for taking AI seriously as a threat to humanity (Vox article by Kelsey Piper). This report on existential risk from power-seeking AI, by Open Philanthropy's Joe Carlsmith, lays out a detailed set of premises that would collectively imply the problem is a serious one. ↩

-

The order of goodness isn't absolute, of course. There are versions of "Adversarial Technological Maturity" that could be worse than "Misaligned AI" - for example, if the former results in power going to those who deliberately inflict suffering. ↩

-

Part of the reason for this is that faster-moving, less-careful parties could end up quickly outnumbering others and determining the future of the galaxy. There is also a longer-run risk discussed in Nick Bostrom's The Future of Human Evolution; also see this discussion of Bostrom's ideas on Slate Star Codex, though also see this piece by Carl Shulman arguing that this dynamic is unlikely to result in total elimination of nice things. ↩

-

See page 191. ↩

-

E.g., see this section of Digital People Would Be An Even Bigger Deal. ↩

-

One relevant paper: Public Policy and Superintelligent AI: A Vector Field Approach by Bostrom, Dafoe and Flynn. ↩

-

Adversarial Technological Maturity refers to a world in which highly advanced technology has already been developed, likely with the help of AI, and different coalitions are vying for influence over the world. By contrast, "Competition" refers to a strategy for how to behave before the development of advanced AI. One might imagine a world in which some government or coalition takes a "competition" frame, develops advanced AI long before others, and then makes a series of good decisions that prevent Adversarial Technological Maturity. (Or conversely, a world in which failure to do well at "competition" raises the risks of Adversarial Technological Maturity.) ↩

-

See definitions of this problem at Wikipedia and Paul Christiano's Medium. ↩

-

A more detailed, private survey done for this report, asking about the probability of "doom" before 2070 due to the type of problem discussed in the report, got answers ranging from <1% to >50%. In my opinion, there are very thoughtful people who have seriously considered these matters at both ends of that range. ↩

-

Some discussion of this topic here: Distinguishing definitions of takeoff - AI Alignment Forum ↩

-

Some more thought on "when money isn't enough" at this old GiveWell post.. ↩